Toxic algae bloom might be largest ever

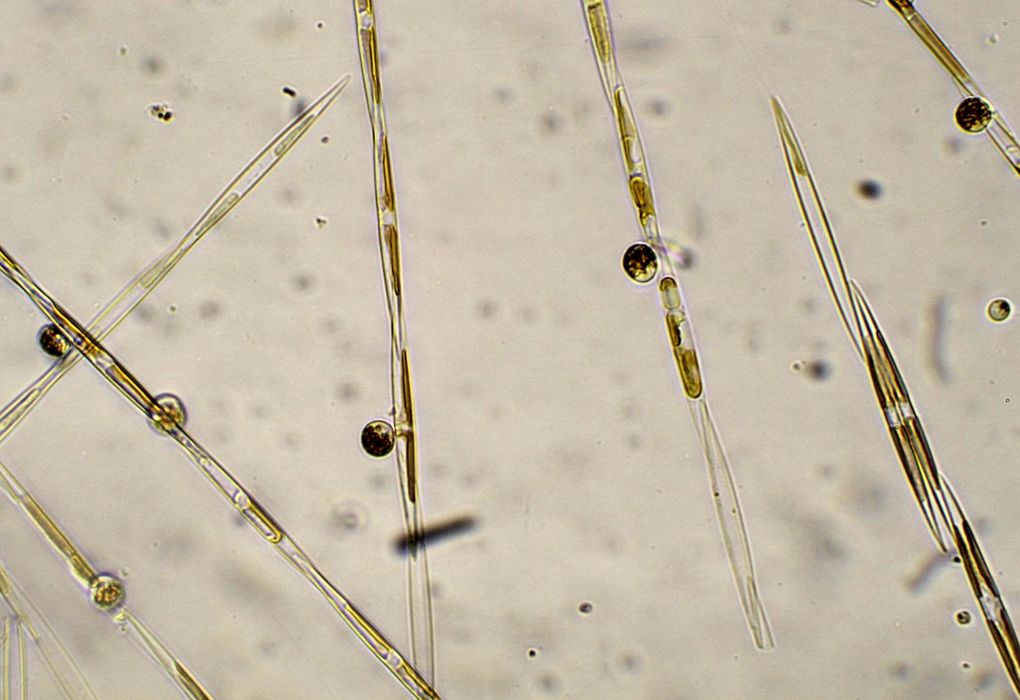

Scientists onboard a NOAA research vessel are beginning a survey of what could be the largest toxic algae bloom ever recorded off the West Coast.

A team of federal biologists set out from Oregon Monday to survey what could be the largest toxic algae bloom ever recorded off the West Coast.

The effects stretch from Central California to British Columbia, and possibly as far north as Alaska. Dangerous levels of the natural toxin domoic acid have shut down recreational and commercial shellfish harvests in Washington, Oregon and California this spring, including the lucrative Dungeness crab fishery off Washington’s southern coast and the state’s popular razor-clam season.

At the same time, two other types of toxins rarely seen in combination are turning up in shellfish in Puget Sound and along the Washington coast, said Vera Trainer, manager of the Marine Microbes and Toxins Programs at the Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Seattle.

“The fact that we’re seeing multiple toxins at the same time, we’re seeing high levels of domoic acid, and we’re seeing a coastwide bloom — those are indications that this is unprecedented,” Trainer said.

Scientists suspect this year’s unseasonably high temperatures are playing a role, along with “the blob” — a vast pool of unusually warm water that blossomed in the northeastern Pacific late last year. The blob has morphed since then, but offshore waters are still about two degrees warmer than normal, said University of Washington climate scientist Nick Bond, who coined the blob nickname.

“This is perfect plankton-growing weather,” said Dan Ayres, coastal shellfish manager for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Domoic-acid outbreaks aren’t unusual in the fall, particularly in razor clams, Ayres said. But the toxin has never hit so hard in the spring, or required such widespread closures for crabs.

“This is new territory for us,” Ayres said. “We’ve never had to close essentially half our coast.”

Heat is not the only factor spurring the proliferation of the marine algae that produce the toxins, Trainer said. They also need a rich supply of nutrients, along with the right currents to carry them close to shore.

Scientists onboard the NOAA research vessel Bell M. Shimada will collect water and algae samples, measure water temperatures and also test fish like sardines and anchovies that feed on plankton. The algae studies are being integrated with the ship’s prime mission, which is to assess West Coast sardine and hake populations.

The ship will sample from the Mexican border to Vancouver Island in four separate legs.

“By collecting data over the full West Coast with one ship, we will have a much better idea of where the bloom is, what is causing it, and why this year,” University of California, Santa Cruz ocean scientist Raphael Kudela said in an email.

He and his colleagues found domoic-acid concentrations in California anchovies this year as high as any ever measured. “We haven’t seen a bloom that is this toxic in 15 years,” he wrote. “This is possibly the largest event spatially that we’ve ever recorded.”

On Washington’s Long Beach Peninsula, Ayres recently spotted a sea lion wracked by seizures typical of domoic-acid poisoning. The animal arched its neck repeatedly, then collapsed into a fetal position and quivered. “Clearly something neurological was going on,” he said.

Wildlife officials euthanized the creature and collected fecal samples that confirmed it had eaten prey — probably small fish — that in turn had fed on the toxic algae.

Ayres’ crews collect water and shellfish samples from around the state, many of which are analyzed at the Washington Department of Health laboratory in Seattle. DOH also tests commercially harvested shellfish, so consumers can be confident that anything they buy in a market is safe to eat, said Jerry Borchert, the state’s marine biotoxin coordinator.

But for recreational shellfish fans, the situation has been fraught this year even inside Puget Sound.

“It all really started early this year,” Borchert said.

Domoic-acid contamination is rare in Puget Sound, but several beds have been closed this year because of the presence of the toxin that causes paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) and a relatively new threat called diarrhetic shellfish poisoning (DSP). The first confirmed case of DSP poisoning in the United States occurred in 2011 in a family that ate mussels from Sequim Bay on the Olympic Peninsula, Borchert said.

But 2015 is the first time regulators have detected dangerous levels of PSP, DSP and domoic acid in the state at the same time — and in some cases, in the same places, he said. “This has been a really bad year overall for biotoxins.”

Over the past decade, Trainer and her colleagues have been working on models to help forecast biotoxin outbreaks in the same way meteorologists forecast long-term weather patterns, like El Niño. They’re also trying to figure out whether future climate change is likely to bring more frequent problems.

At a recent conference in Sweden on that very question, everyone agreed that “climate change, including warmer temperatures, changes in wind patterns, ocean acidification, and other factors will influence harmful algal blooms,” Kudela wrote. “But we also agreed we don’t really have the data yet to test those hypotheses.”

On past research voyages, Trainer and her team discovered offshore hot spots that seem to be the initiation points for outbreaks. There’s one in the so-called Juan de Fuca Eddy, where the California current collides with currents flowing from the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Another is Heceta Bank, a shallow, productive fishing ground off the Oregon coast, where nutrient-rich water wells up from the deep.

“These hot spots are sort of like crockpots, where the algal cells can grow and get nutrients and just stew,” Trainer said.

Scientists have also unraveled the way currents can sweep algae from the crockpots to the shore. “But what we still don’t know is why are these hot spots hotter in certain years than others,” Trainer said. “Our goal is to try to put this story together once we have data from the cruises.”

Read the original post: http://www.seattletimes.com