— Posted with permission of SEAFOODNEWS.COM. Please do not republish without their permission. —

SEAFOODNEWS.COM [San Francisco Chronicle] by Lizzie Johnson – August 21, 2015

Long before scientists and shellfish companies were aware of what was happening, a silent killer began devastating California’s oyster industry.

About 10 years ago, baby oysters, or spat, began to die at an alarming rate. Farms along the West Coast lost more than half of their bivalves before they reached maturity, creating a shortage of seed. That deficit hit Hog Island Oyster Co. in Marshall especially hard.

So owners Terry Sawyer and John Finger began collaborating with UC Davis’ Bodega Marine Laboratory to figure out what was plaguing the water in Tomales Bay, their backyard.

After more than two years of tests, they have a better understanding of the condition afflicting West Coast oysters, mussels and clams. But there is trouble ahead for California’s shellfish industry as it faces the threat of species extinction.

“We are talking about something that’s going to happen in my lifetime and my children’s lifetime,” said Tessa Hill, an associate professor of geology at UC Davis. “We are going to see dramatic changes in terms of what animals can be successful on the California coast because of ocean acidification.”

That culprit, ocean acidification, is the caustic cousin of climate change, and it shifts the chemistry of ocean water, making it harder for oysters to grow. That’s because about 30 percent of the carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere is absorbed by the ocean, causing pH levels to plummet and making the water more acidic. The more pollution in the air, the more carbon dioxide the ocean absorbs.

Larval stage stunted

The hostile conditions stunt the growth of oysters in the larval stage, making it difficult to build their fragile calcium carbonate shells. If acidification doesn’t kill them outright, an increased susceptibility to disease and predators often will. The stress also weakens many small oysters, so it takes them longer to reach reproductive age.

“It’s definitely scary,” said Zane Finger, who runs the Marshall oyster farm for his father, John. “If you’re doing any kind of job that depends on the environment, whether it’s farming on land or farming in the water, it can be uncertain. Things are changing, and it makes me nervous about the future of this business.”

Oyster growers in Oregon were the first to sound the alarm 10 years ago on ocean acidification. Whiskey Creek Shellfish Hatchery, based in Oregon’s Netarts Bay, and Oregon State University were among the first to work together and publish research on the phenomenon. They established the link between acidification and the collapse of oyster seed production.

Dire prediction

“It was one of the first times that we have been able to show how ocean acidification affects oyster larval development at a critical life stage,” OSU chemical oceanographer Burke Hales said in a statement. He was a co-author on one of the first studies in Oregon. “The predicted rise of atmospheric carbon dioxide in the next two to three decades may push oyster larval growth past the break-even point in terms of production.”

And in 2010, a mix of scientists and industry partners formed the California Current Acidification Network (C-CAN), which works for more research on acidification. UC Davis and Hog Island, both members, have helped expand research along the coast. The relationship has helped Hog Island prepare for future water conditions and allowed the university to conduct research on the link between climate change and acidification.

For the first two years of the company’s collaboration with Hill, data were collected only once a month from a buoy in the estuary. Then the federal Central and Northern California Ocean Observing System (which goes by the mile-long acronym of CeNCOOS), offered to upgrade the system.

Now, it’s a round-the-clock operation that gives minute-by-minute data on water conditions. Hill runs a small lab tucked in the back of a shed at Hog Island’s Marshall oyster farm. The structure is damp and filled with loudly whining equipment. Tubes pump seawater directly in from the bay so the team can closely monitor changes in acidity, salinity, temperature and oxygen.

‘Stressful for oysters’

“You can get up in the morning and look at the charts and say, ‘Oh, the water is stressful for the oysters today,’” Hill said, pointing to a zigzagging line on the computer screen. “It gives them real-time information and a big picture of what’s happening in the bay.”

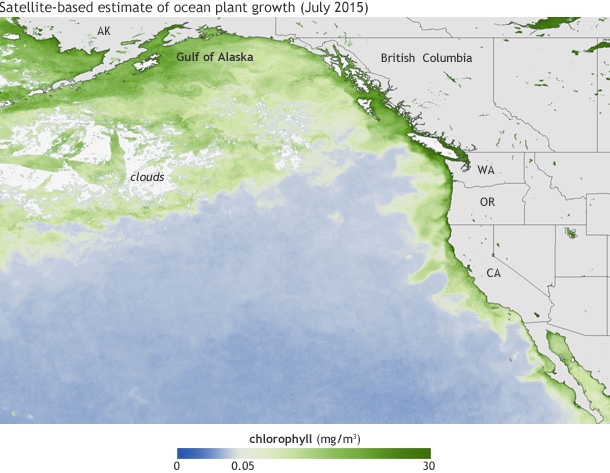

They’ve learned that the high acidity in the water is related to seasonal upwelling, or when the wind pushes surface water offshore, allowing the deeper, more acidic water to rise up. For now, hatcheries can grow spat during spring and summer, considered the off seasons. But by 2030, upwellings are expected to last longer, and by 2050, they could occur year-round, Hill said.

“The rate of change is something that we have never seen before as a planet,” Sawyer said. “And it’s measurable; you can’t argue with that. We have the data. We should pay attention to it now, immediately, and not later.”

High mortality rate

The mortality rate for baby oysters is still high — anywhere from 50 to 100 percent. But oyster companies have learned to compensate for it by growing more spat in different locations. They’ve also put a quota on the amount of shellfish customers can buy. Diversifying will hopefully prevent another shortage like the one that hit from 2007 to 2010.

Sawyer and John Finger are planning to expand the company’s aquaculture operation. Within the next two years, they will open a $1.5 million oyster hatchery in Humboldt Bay. It will provide seeds to grow in Tomales Bay and, eventually, harvest some of its own oysters as well. Permits have been approved, and cultivation will start later this year.

A day on the farm

For now, operations at Hog Island Oyster Co.’s Marshall farm remain the same. Most mornings, workers slide on their rubber waders and guide a flat-bottomed boat onto the water. Then they slosh to the oyster racks nestled on the muddy floor, dragging them to the surface with long hooks. The smell of musty water and saltwater fills the air as they work.

Soon — and Sawyer hopes for a long time — those oysters will make their way to someone’s plate.

“I care about this on so many levels,” he said. “From a farming point of view, from business, from caring about my kids and the future generations who will have to deal with this. We live in a pretty amazing world, and I would like to preserve that as much as possible.”

Subscribe to: SEAFOODNEWS.COM

NASA Animation shows the wide variance in sea level rise in recent years. The pale coloration along the West Coast illustrates a lower rate of rise. (NASA Scientific Visualization Studio)

NASA Animation shows the wide variance in sea level rise in recent years. The pale coloration along the West Coast illustrates a lower rate of rise. (NASA Scientific Visualization Studio) Video: https://youtu.be/rkCzae-FCek

Video: https://youtu.be/rkCzae-FCek