California’s Squid Fishery: The Largest in the U.S. and an Economic Powerhouse

CWPA sponsors seasonal squid paralarvae surveys in cooperation with the Department of Fish and Wildlife to document the environmental variability in market squid abundance and ensure a sustainable fishery. For more information on CWPA’s squid research program, please check out our Research link https://californiawetfish.org/squid-research.

by Katherine Clements, originally published in The Log

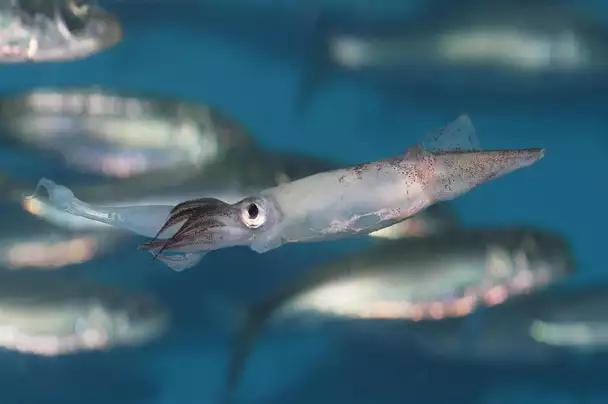

California holds a unique distinction in the United States as home to the largest squid fishery by both volume and revenue. While most Americans might think of squid as a side dish or appetizer at seafood restaurants, in California, market squid fishing has a deep-rooted history and serves as a significant contributor to the state’s commercial fishing economy. California’s market squid (Doryteuthis opalescens), commonly known as opalescent squid, not only drives revenue and jobs in the fishing industry but also exemplifies how sustainable practices are becoming integral to modern fisheries. From humble beginnings to MSC-certified status, California’s squid fishery is a fascinating example of how one invertebrate species has created waves in the fishing world.

The market squid fishery in California traces back to the late 1800s when it was first established by Chinese immigrant communities. Squid were traditionally caught along the Monterey coast and processed in drying sheds before being shipped to markets in Asia. By the early 20th century, Italian and Portuguese fishers had also joined the fishery, contributing their own techniques and expanding the industry’s reach. Over the decades, demand for California squid has grown substantially, both domestically and internationally.

While the fishery has had its ups and downs due to natural fluctuations in squid populations, advancements in fishing technology and increased demand in global markets has helped transform the fishery from a small-scale industry into a commercial powerhouse by the late 20th century. By the 2000s, California’s market squid fishery had not only stabilized but had become one of the largest and most profitable fisheries in the state. The industry now generates millions in revenue annually, rivaling other prominent California fisheries such as Dungeness crab.

As of 2022, California’s market squid fishery reported an astonishing catch volume of over 147 million pounds, which translates to approximately $88 million in revenue. These numbers alone highlight the economic power of the fishery, yet it’s even more impressive when compared to other notable fisheries.

Since the year 2000, revenue from California’s market squid has consistently outpaced the combined catch value of other major species, including Pacific mackerel, jack mackerel, northern anchovy, and Pacific sardine. The high volume and demand for market squid make it an essential part of California’s fishing economy, supporting jobs not only for fishers but also for workers in processing, transport, and export.

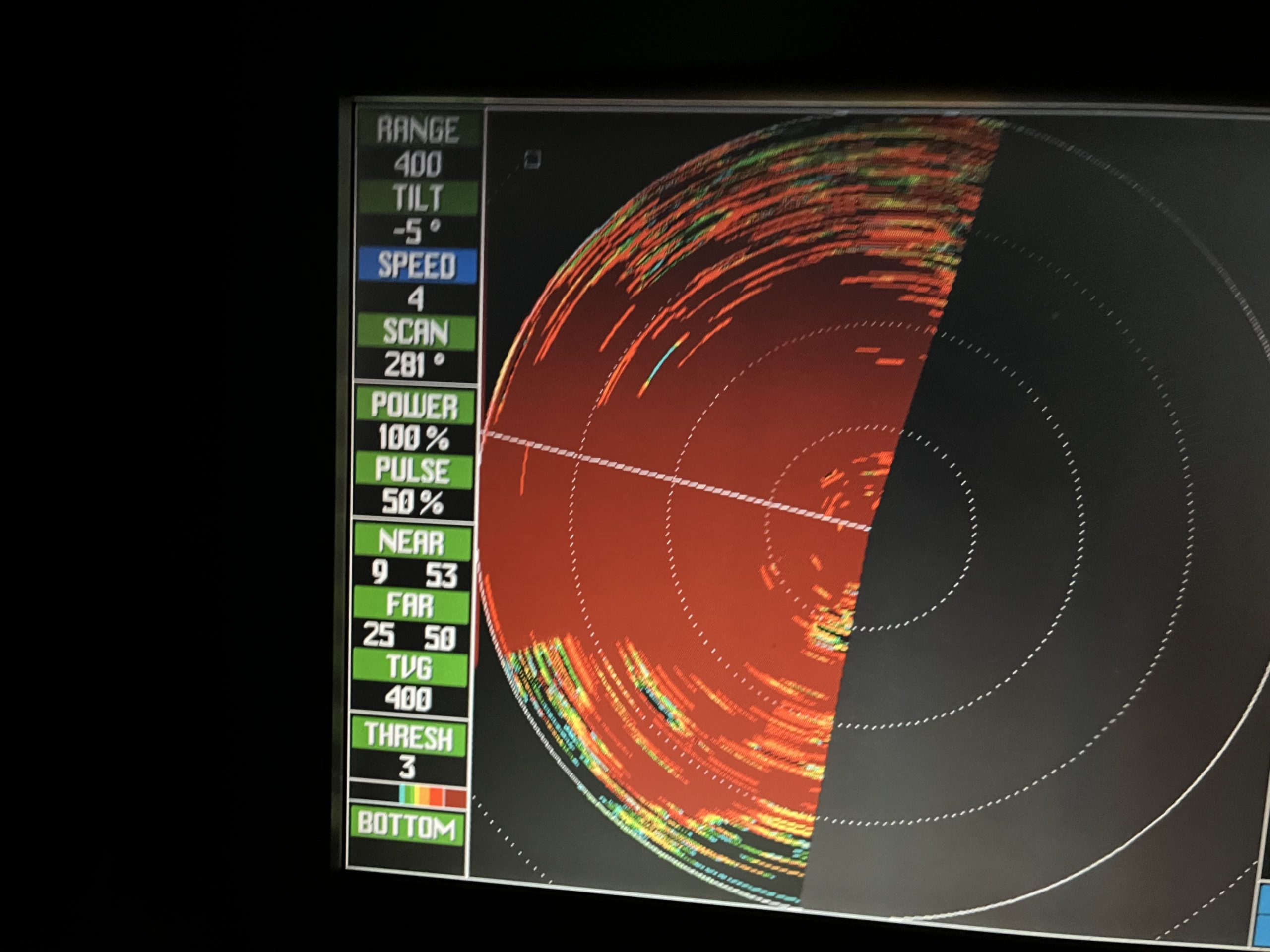

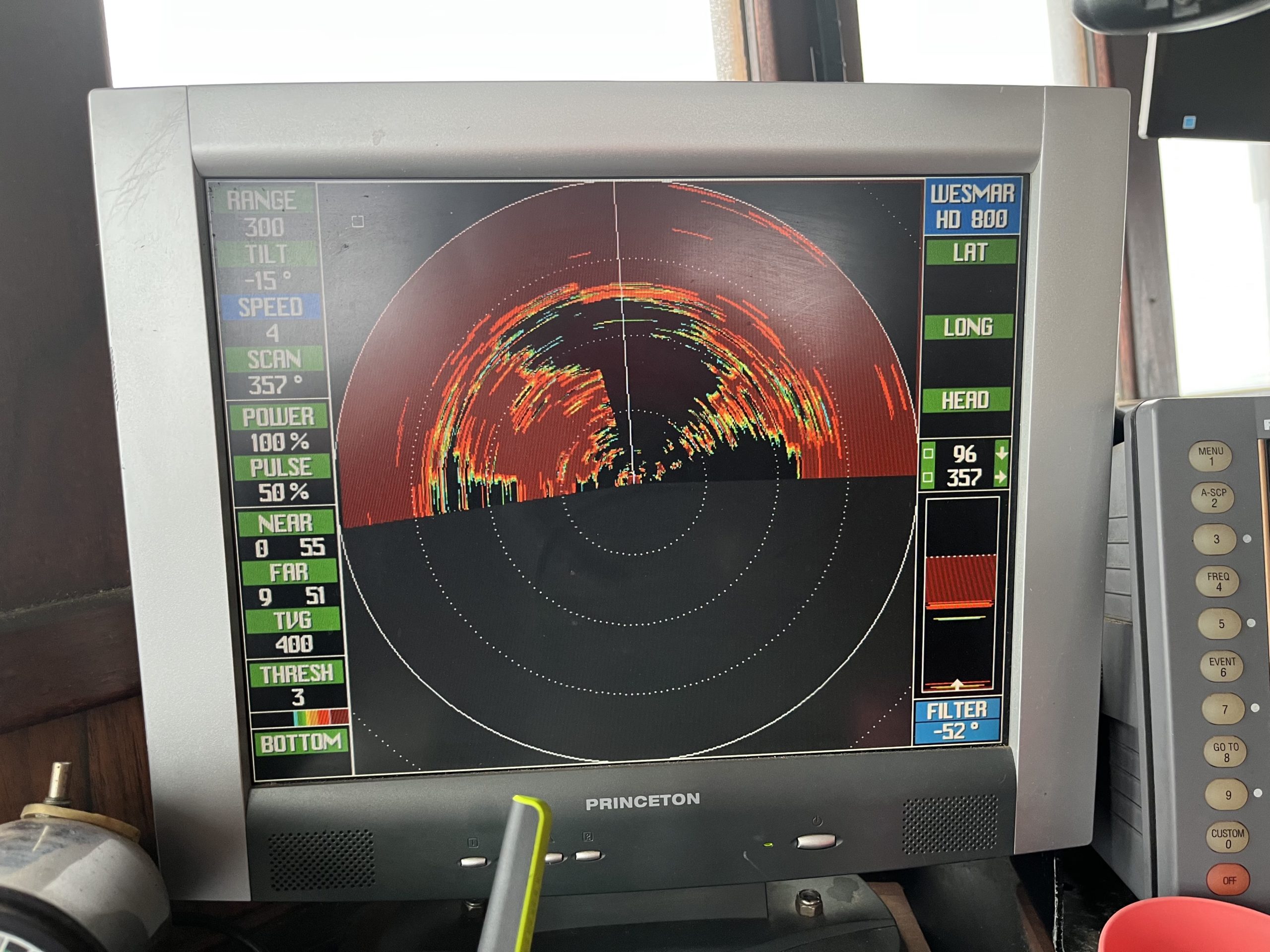

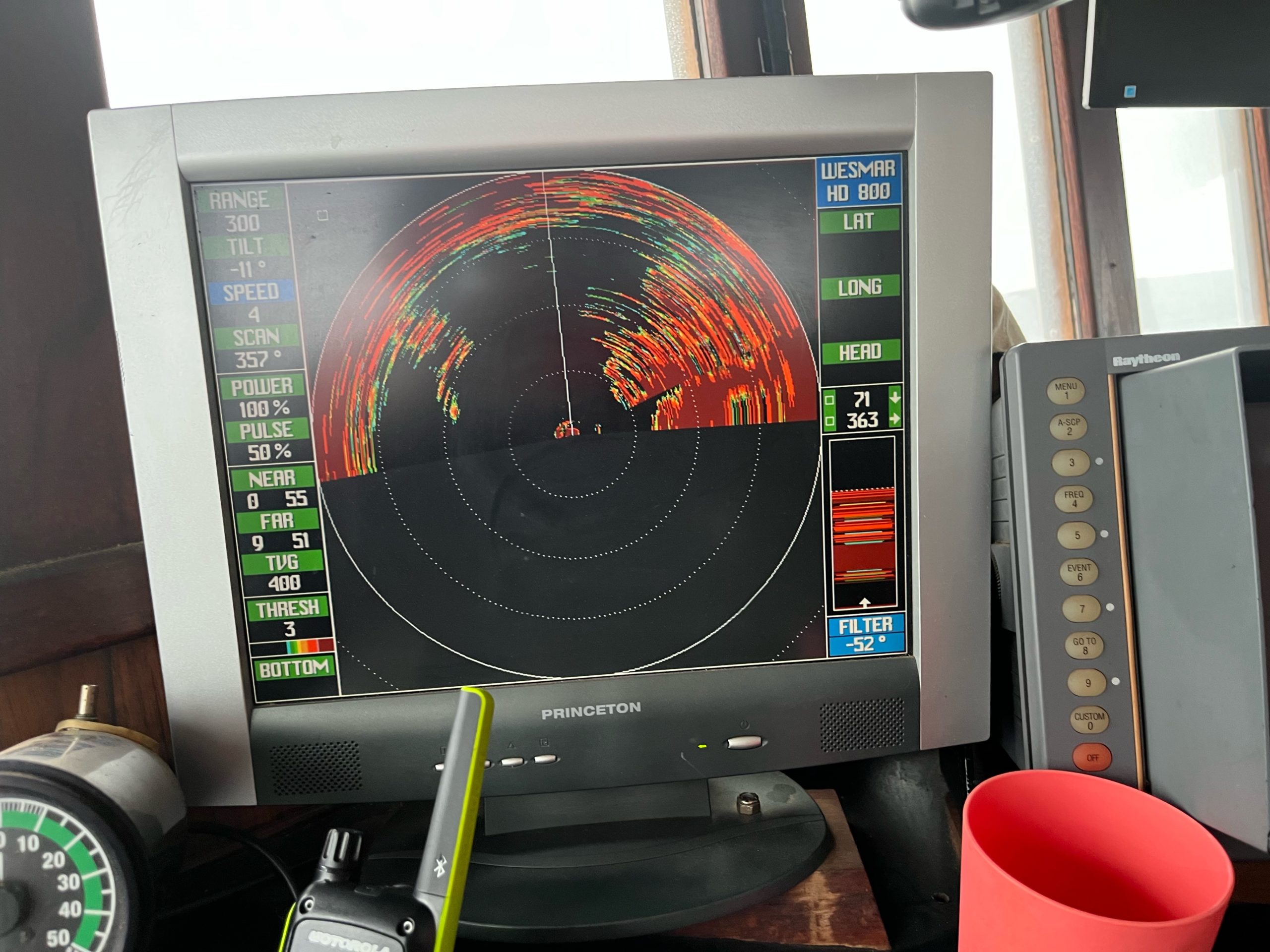

California squid are primarily caught in the waters off Southern and Central California, from Santa Barbara down to San Diego. The season, which generally runs from April to October, is marked by large-scale operations involving purse seine boats and specialized lighting systems that attract the squid to the surface for easier capture. These operations are carried out by a fleet of commercial vessels, some of which have been involved in the industry for generations.

The economic benefits of California’s market squid fishery extend well beyond the coast. Squid processing plants, mainly concentrated in Southern California, provide jobs for hundreds of workers who process the catch for both domestic and export markets. Much of the California market squid is frozen and exported to Asia, where it is a staple in many cuisines. Some of it remains within the U.S., catering to growing demand for seafood and the rising popularity of squid-based dishes.

The importance of sustainable fishing practices has never been more relevant, especially for a fishery as large as California’s. Recognizing the impact that overfishing can have on marine populations and ecosystems, California’s fishery managers and industry leaders have implemented several policies to ensure the market squid population remains healthy and resilient.

One of the key measures in place is a weekend closure system, where squid fishing is prohibited from Friday evening through Sunday. This ensures that the squid have an uninterrupted window for reproduction, as squid spawn and lay eggs in shallow waters. The closure period is a precautionary measure aimed at preserving the stock and allowing for a consistent population year after year. In addition, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife has established a seasonal catch limit, known as a harvest cap, to further regulate the fishery and prevent overexploitation.

In 2023, the California market squid fishery achieved Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certification, a prestigious designation that recognizes sustainable practices in fisheries worldwide. MSC certification is based on criteria like the health of fish stocks, effective fisheries management policies, and minimal environmental impact. The certification not only reinforces California’s commitment to sustainability but also enhances the marketability of California squid, appealing to eco-conscious consumers around the globe.

The MSC certification has brought California’s squid fishery into the spotlight as a model for responsible fishing practices. The fishery’s success is attributed not only to environmental management but also to the cooperation between commercial fishers, regulatory bodies, and scientific communities who work together to monitor and manage the stock effectively.

California market squid may not always appear on American dinner tables, but its popularity is rising. Globally, squid is highly prized in cuisines across Asia, Europe, and Latin America. California squid, however, tends to be smaller than the Humboldt and Patagonian squid commonly consumed in the U.S., which are sourced from Mexico and Peru. While these larger squid are preferred for certain dishes, California market squid is widely used in Asian cuisine, where it is valued for its tender texture and delicate flavor. In Japan, China, and South Korea, California squid is a popular ingredient in dried and prepared forms, making it a key export product.

The squid’s small size, however, also lends itself well to dishes like calamari, a favorite appetizer in the United States. The demand for calamari in restaurants and seafood markets has contributed to the steady popularity of California market squid. Although a relatively inexpensive catch, the high demand for squid on an international level makes it a valuable resource. Its versatility in various cuisines makes squid an increasingly popular choice among seafood lovers looking for a sustainable and low-fat protein.

California’s squid fishery also provides opportunities for recreational fishers who seek a different experience from the typical coastal catch. Squid fishing, especially at night, is a unique experience for anglers who appreciate the thrill of catching a different species. Many charter boats along the California coast offer night fishing trips specifically targeting market squid, using powerful lights to attract the squid to the surface. These excursions are particularly popular among novice anglers and families looking for a fun, accessible introduction to fishing.

The gear required for squid fishing is minimal, making it a low-cost activity. Anglers usually need only a light rod, a jig, and a headlamp or flashlight to participate. The peak season for recreational squid fishing coincides with the commercial season, and several areas along the California coast, such as Monterey and Ventura, have become hotspots for squid fishing. Recreational fishing for squid not only supports local economies by driving tourism but also promotes an appreciation for California’s marine resources and sustainable fishing practices.

While California’s market squid fishery is generally considered well-managed and sustainable, it is not without its challenges. Like many marine species, squid populations can be affected by environmental factors such as temperature fluctuations, ocean acidification, and changes in food availability. Squid are highly sensitive to environmental shifts, and climate change poses a potential risk to their reproductive patterns and migration habits.

To ensure long-term sustainability, researchers and fishery managers continue to study the impacts of environmental changes on squid populations. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife works closely with scientific institutions to monitor squid stocks, study spawning habits, and adjust management practices based on research findings. In recent years, the state has implemented adaptive management strategies, including adjusting the harvest cap and seasonal regulations based on stock assessments and environmental data.

As the world’s demand for sustainable seafood continues to grow, California’s market squid fishery stands out as an example of how responsible fishing can benefit both the economy and the environment. The fishery’s economic significance, paired with MSC certification and strong management practices, positions California market squid as a valuable resource with global appeal.

California’s squid fishery is much more than just a business; it is a testament to the state’s commitment to balancing economic growth with environmental stewardship. From its beginnings in the late 1800s to its current status as a leading sustainable fishery, California’s market squid industry has adapted to meet global demand while adhering to conservation principles. Commercial and recreational fishers alike benefit from the accessibility, profitability, and sustainability of this resource, which continues to support local communities, create jobs, and provide a model for fisheries worldwide.

With careful management, ongoing research, and a dedication to sustainable practices, California’s market squid fishery is well-positioned to remain a vital part of the state’s fishing heritage. As more consumers recognize the value of sustainable seafood, the demand for California market squid will likely continue to rise, further strengthening the fishery’s role in California’s economy and contributing to the future of global seafood sustainability.